'Take-away' is a studio run by High Holdings a project by Valle Medina and Benjamin Reynolds, directors of Pa.LaC.E. 'Take-away' is currently at the Royal College of the Arts, London.

Enquiries: ho@ldin.gs

IG: @ho.ldin.gs

Website: SN 1006

Last year, ADS12 used overabundance as a deployable phenomena in the formation of architectural spaces. Projects were considered “plentitudes”, consisting of a minimum of two-thousand “acts” (eg. species, subjects, objects, processes and so on). This year projects will enact promises of strategic omissions, willful refraining and absences. Instead of perpetuating how architecture normally conflates acts of removal or reduction via the aesthetic, we’ll explore the potential of good in loss, or development without growth, or whether deprival can produce new vantages from which to grapple the widening gap between our biological shortcomings and the violence of information - a long term goal of the studio.

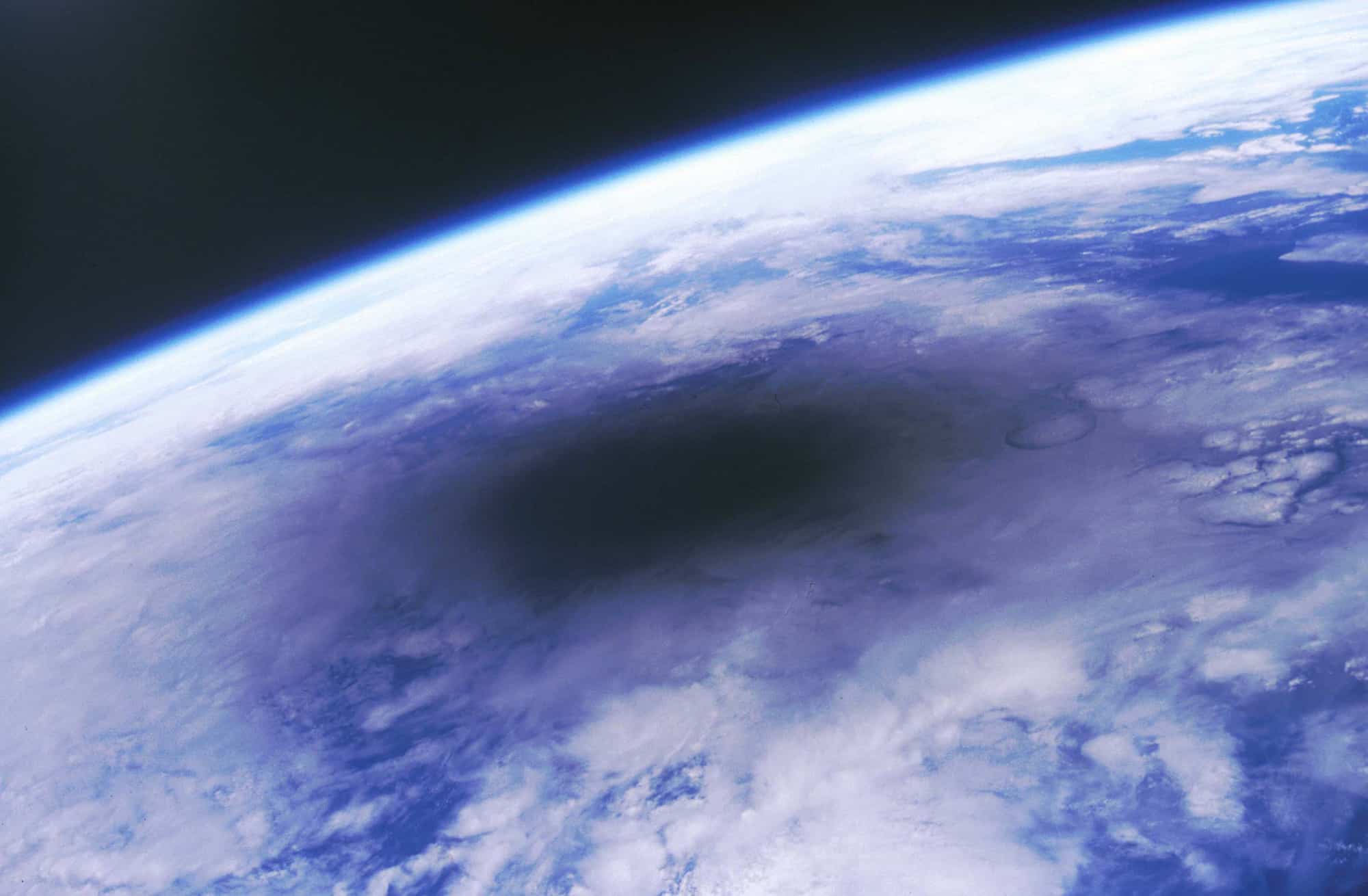

Fig.01: The ultimate deprival: a momentary glimpse of the sun’s death. 11 August 1999. The total eclipse. immortalised by French astronaut Jean-Pierre Haigneré from the Mir station. Source: cnes.fr.

The deprival of ordinary pleasures has deep roots in many traditions. At designated times of the year, and usually in preparation for an event or purification, both eastern and western traditions encourage some form of asceticism, or abstaining from gratifications through self-restraint. In the case of Christian monastic ideals, the angelikos bios, or the angelic life, formed the code of the life of the monastery. It is considered the highest form of living because angels don’t sleep, eat, or love.

Fig.02: Angels refuse sleep, eat, and love. The angelic life is the code of the Vardzia Cave Monastery, Georgia. Source: maxpixel.net.

Now we’re seeing forms of asceticism emerging as a consequence of the affluence of modern life. The ever-perfecting union of computation and logistics continues to generate more things, quicker; and due to the frictionless rub between trend and production, we keep buying into them. We endlessly create fictional demands; wants where there were no wants. The net result is the triumph of fast-and-insincere as the prevailing culture. The possession of things has been split from necessity, material and manufacturing integrity or even geographic legacies of production. A thing should now last as long as the social realm deems it relevant, or until the idea of the thing has been exhausted by media.

Radical acts of retreat, removal or deprivation are becoming more prevalent as a mechanism by which to confront such accelerated consumption patterns and the gradual loss of free will. This rising asceticism, albeit in a more diluted form, is decoupling itself from its religious origins and is instead used to attain among other things, personal satisfaction. Furthermore, the rise of fasting, celibacy, seclusion, voluntary infliction of pain, abstinence from intoxicants and renunciation of worldly goods is aided by the fact that they are now offered as consumable services.

Fig.03: May 2017 saw the birth and death of the fidget spinner. Flints were first used sometime during the Lower Paleolithic period 3 million years ago in Africa (R). Source: self.com and 163.com.

Media—just as any foodstuff—is consumed in a diet, we stomach, we regurgitate, we binge. We do this because we’re indirectly told that it is right and good to digest more, but clearly there is information that is more or less nutritious. This relentless ingestion of information now impregnates a digital membrane over what was once a romantic idea that architectural space is just plain material. Especially in leisure infrastructures, the overlay of spatial pleasures with the digital analytics of behaviour fuses especially well. Take the casino: most offer a rewards scheme, enticingly labelled as a "gold card" or maybe it’s platinum. With that, the casino can track your tendencies (and make claims about you): they know that you choose 23 on roulette (you’re superstitious), you normally stop when you’re 300 in the hole (you’re somewhat responsible), you take more risks on Fridays (because you drink), you once assaulted a dealer (because you have anger management issues), you often stay for five hours (because you have children), you eat the lobster (you’re a Taurus), you stay alone (so you’re divorced), you go to your room at 2 am in the adjoining hotel (you don’t have custody of your children), you come roughly every 3 weeks (if not, they email you), it takes you 40 mins to get there (you’re middle class).

Fig.04: The gold card of the Wynn Casino in Las Vegas contributes to as much spatial information than the very walls of the Wynn casino.

Such a saturation of information results in spaces that are not mere material, but in fact predictive behavioural containers drenched in our identities. It is no wonder then we also purge. Take-away will explore emerging movements to erase behaviours, histories and cultures at the personal and social level. Part of that exploration is to denounce whether such a movement has negative causes (eg. does it eradicate the meaning of a place, see Rio Tinto's destruction of a 46,000-year-old Aboriginal heritage site in Pilbara, Western Australia) or does it have a positive outcome (eg. liberating someone to ‘start again’, see the Witness Protection Program).

As the imminent but slow loss of nature dawns upon us, part of our shared reality will be to accept living with its absence. Organisms under changing conditions, like the irresistible danger of flooding or combustion, make adjustments to their own constitution: its temperature, systems of protection, its proportions and so forth. In the same way organisms seek balance with their context, projects within Take-away will seek to adjust to given contexts given speculative scenarios of absence.

We are often reminded that a potential lack of health, safety or comfort is a plausible threat in need of our addressing, but could we create unexplored scenarios in which deprivation is celebrated? Lack is already naturalised within geography (ie. less UV radiation the further away we are from the tropics), in others lack fluctuates (ie. periods of drought), it can be anticipated (ie. signified by the construction of silos as premonition of a future shortage) or orchestrated over time (ie. resulting in a pension plan). Sometimes idealised by “cleanse gurus”, the removal of excess may be a practice that promotes healthy growth (ie. the pruning of trees), or it may be culturally integral (ie. the ritualised cleaning of gravestones in Japan).

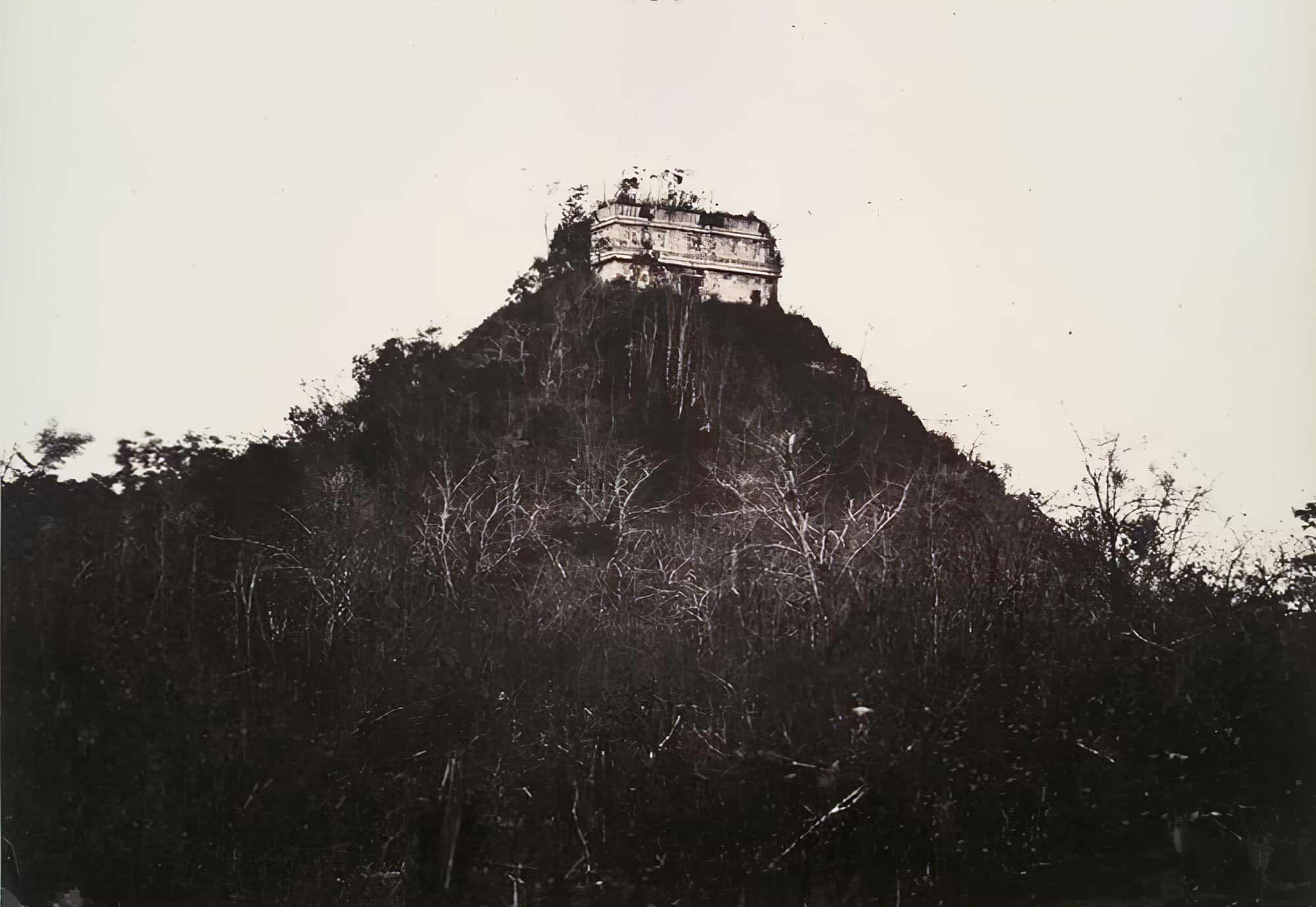

Fig.05: Kukulkán Pyramid, Chich'en Itza, Mexico, prior to the unearthing of its base. Source: stringfixer.com.

Loss in western cultures has always been something to be mourned. Indeed the nineteenth century has sometimes been called the golden age of mourning. Lavish funeral rituals and funerary architecture commemorate a time when rituals of private lamentation coincided with a public grieving process. Gradually, the twentieth century slowly grew to hide the realities of death, and ceased to devote time to the process of coming to terms with loss (Ariès). This year we’ll address how the act of taking-away firstly implies the identification of what is lacking, waste, defective, of no use or of less worth. We’ll explore how taking-away can take place violently or through a slow replacement over time. We’ll also learn what are some strategies to remove and to refuse.

Fig.06: Upon scanning your IC card, your relative’s urn is automatically retrieved from a storage rack, and presented at this private worship room. Source: Daifuku Logistic Solutions.

It is not the aim of the class to imagine scenarios composed of just one characteristic, in the case of competition it would realise a monopoly, and in the case of a species: a monoculture. A single language that would impose itself, no matter how unique, as a universal language, would create terror; ‘a world [as] a barbarous wasteland, unlivable’ (Serres). Nor is it the aim of the studio to promote ideas of "living simple", thriftiness or aesthetic judgments pertaining to “minimalism”. Instead, projects will begin by identifying and then depriving or impairing otherwise indispensable conditions—either biological, social, meteorological, material, etc.—of a precise location. In doing so, it will create new contexts with heightened social, political or ecological relations from which the architectural projects will emerge.

In 2021/22, “Take-away” will again be hosted within High Holdings—http://ho.ldin.gs/—an environment for the generation of architectural discourse addressing the unfolding depictions of the world that may appear unrecognisable, but are truly products of terrestrial occupation. By prioritising the sovereignty of the architectural idea, High Holdings continues to explore the growing distance between information and (over-)looking; complexity and (mis-)understanding; contribution and (non-)participation. Previously in “CHRONOCOPIA” (2018-9) explored how to characterise time within the architectural project in order to perceive the speed of the present,“Sight/Seeing” (2019-20) put the conspicuity of the Image on trial and “Melee” (2021-22) developed projects as plenitudes challenging our own perceptive shortcomings.